Olla Meah (center) served for the British in “V” Force during WWII. He was a Rohingya community leader in the 1940s during Burma’s Independence. His son (upper left) became a teacher.

In the mid-1950s, the first National Registration Cards issued in Burma were issued in a pilot program starting in North Arakan. His ID card number is 00025. It is believed Olla Meah was issued one of the earliest NRC cards.

“My father worked for the government since 1944. He was a volunteer and was responsible for distributing rations during the British Administration. After independence he joined the Customs Department. He retired in 1966. The National Registration Card (NRC) provided to my father is numbered, 000025. It is the 25th NRC card issued in the whole of Burma. If my father was not a citizen, he could not have this card and a government job. My grandfather, great grandfather and great-great grandfather were born in this country and we are descendants of them.”

Mirza A, 61

Son of Olla Meah

Land documents, land tax payments and legal land settlements from Attar’s family date back to the early 1900’s. The documents also show Rohingya land ownership in the 1800s.

“We are the descendants of a big family from Boli Bazar. These land documents are gathered for Rohingya to show as their evidence. That is why my father and others kept them. Whatever the Burmese government says, we have these documents. If I have these documents, I can tell my family history and I can say that the descendants of this family will never disappear.”

Salai Ahmed (center) was appointed a village headman in 1949. He passed away in the late 1980s. Included here are: original National Registration Cards of Salai Ahmed, his brother and son and their wives, a Family list issued in 1959 and Appointment of Headman issued in 1949. Also two voter registration cards issued in 1978 and 1981 by the electoral commission.

“My grandfather was a village headman for almost 40 years. He was an Arabic school teacher. He was respected by many people and was a member of the local council. My family owned a lot of land and we lived in Maungdaw for several generations.”

Rohim U,

Grandson of Salai Ahmed.

Ula Mea (upper right) became a policeman in 1952. He was highly decorated for his service. In the 1950s, armed insurgencies were occurring throughout Burma, including in Arakan, which were referred to by the Burmese press as Mujahids. In 1956/57, Ula Mea was responsible for the arrest of a leading Mujahid commander in Arakan.

Included are Ula Mea’s policeman ID, Good Service Certificates, Police ‘Do’s & Don’t’ book. After retiring he received a government pension. His pension book is also included.

“My grandfather was a policeman and my father was a policeman…a sergeant. He retired in 1995. We were so proud of him. That is why my brothers also served in the police and my brother-in-law in the military. We were proud of them for their service for the country.”

Gura M

Grandson of Ula Mea

Taza Mulluk was born in 1941. In 1961, he became a government employee at Burma Telecommunication Service. He then became a postman. In 1965, he was forced to change his name to a Burmese name, U Ba Tun.

He retired as a postman and received a government pension. Included are ID cards from his employment at Burma Telecom and Burma Postal Service, his pension book and NRC card, a list of all the postmen in Arakan at that time and a photo of Taza Mulluk retired with two other colleagues from the postal service.

“My grandfather received his uniform from the government. I saw his uniform when it was put out to dry under the sun. I used to think to myself whether he was in the military or the police. My parents told me he was a postman. He got sick and I had to accompany him wherever he went. I remember seeing the Rakhine respect my father by putting their heads down when we went out on the road.”

Mohammed A (23)

Grandson of Tullah Muzak

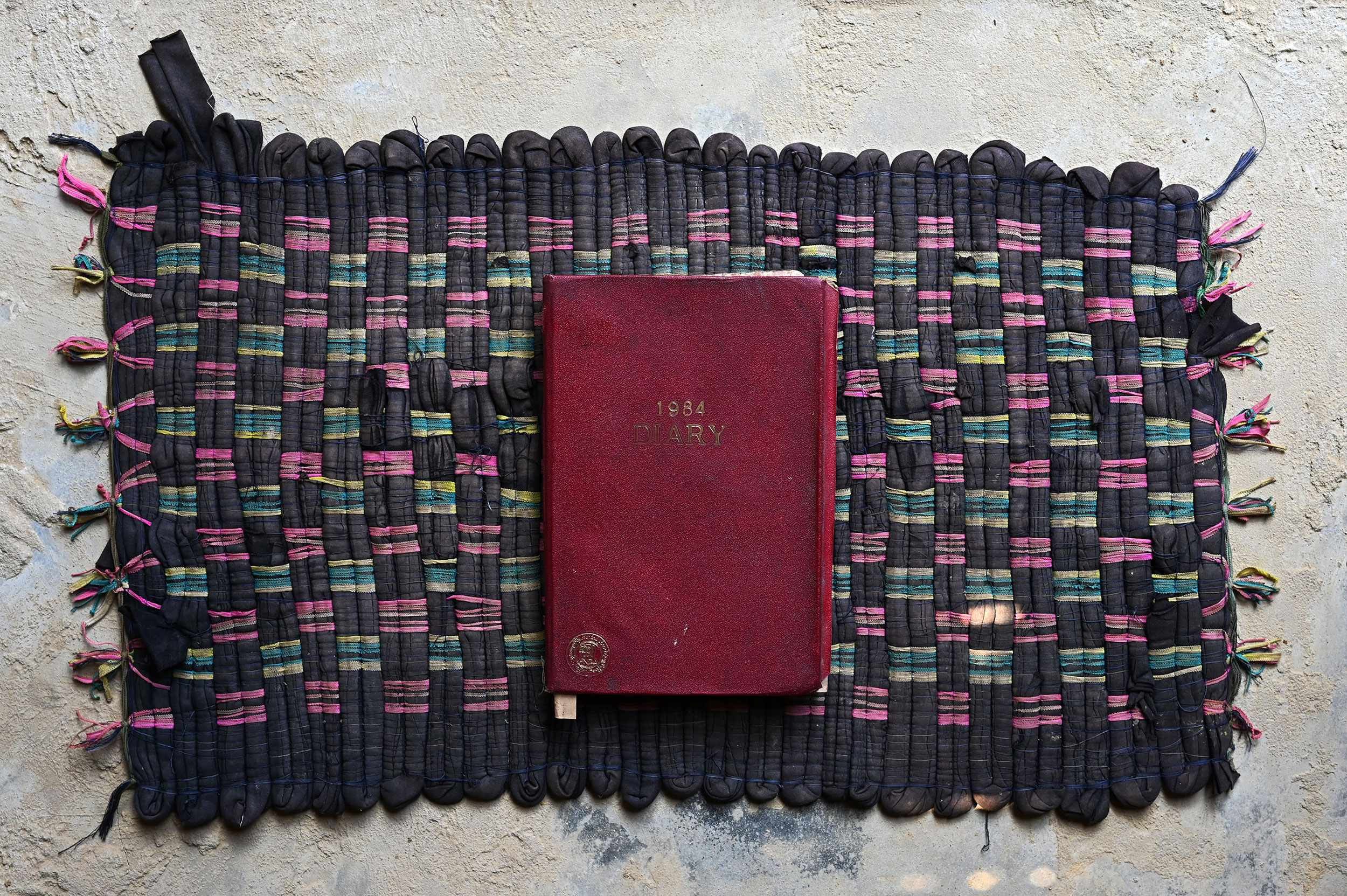

It took several years for the government to implement the 1982 Citizenship Law. In 1984, Abul Kalam attended a meeting where government officials informed village leaders about the 1982 Citizenship Law. He was responsible for communicating the details of the meeting back to others in the surrounding villages near his home. Page after page of Abul’s diary is filled with his notes from that meeting.

“They called us for a meeting to explain the new citizenship law. When the meeting started, the chairman was explaining the law. We were listening and taking note of it. I was writing as much as I could in my diary. Finally, when we learned they were using the citizenship law to discriminate against us, we felt like we were not part of the world anymore.”

Abul Kalam, 69

Mohammed T attended Sittwe University and graduated in 2004 with a degree in Chemistry. Included here: student ID cards, graduation photographs, graduation certificate and program of graduation day events.

“Buddhists and we, Rohingya, we studied together in the past. I am the first person to graduate in my family. That’s why I am very happy. There are a lot of people who couldn’t study like me during our time due to restrictions from the government. But, after getting a degree…the majority didn’t have any opportunities to work. We pursued an education and got a degree then had to sit at home with it. The world doesn’t know there are educated people in the Rohingya community and that Rohingya are not getting the chance to show their skills.”

Mohammed T (42), 2023

“My father told me that long ago we were all the same. We all lived together with other people. My parents said their lives in the past were peaceful times. After I was born, when I was growing up, they said they are getting worried. They told me, These people will drive us out someday. I believe all of these documents are proof that we are originally from Arakan. Look back at all of this and you will see who we are and how long we have been here.”

Nurul B, 60